IMDb RATING

7.6/10

9.1K

YOUR RATING

A group of oppressed factory workers go on strike in pre-revolutionary Russia.A group of oppressed factory workers go on strike in pre-revolutionary Russia.A group of oppressed factory workers go on strike in pre-revolutionary Russia.

Leonid Alekseev

- Factory Sleuth

- (uncredited)

Daniil Antonovich

- Worker

- (uncredited)

Pyotr Malek

- Police Spy

- (uncredited)

Misha Mamin

- Baby Boy

- (uncredited)

Pavel Poltoratskiy

- Stockholder

- (uncredited)

Featured reviews

More so with the Soviets than with any other film school, we need to resupply the context. The image reigns supreme but not in ways we may understand today, as aesthetic accomplishment or space for contemplation. It is about immediate understanding as formed in the eye so that narrative - the tool by which the Czarist or the bourgeois wrote history, thus a suspicious element - is bypassed, the eye and not the mind is thus tasked to construct. Meant to instruct ideological fervor in a generally unsophisticated audience, these films, propaganda we call them now, stirred into action, not thought. This was in tacit understanding with Marxist principles, that demanded history be foremostly changed than understood.

Change; action; seeing. This is the causal chain the Soviets immersed themselves in, looking for the keys that guide vision.

So, these people eventually grew to know more about the mechanisms that control the image than any other group of people anywhere else in history. They were theoreticians, scientists of film, as well as the actual makers; a now extinct combination, much to our dismay. Eisenstein - and Vertov - were key figures; I mean, here was a man who studied Japanese ideograms to understand synthesized image; who discovered that editing to the beats of the human heart affected more.

So, we are talking about a reflexive cinema, about rhythm as opposed to melody. It's just as well with these films that the narrative content is pretty much discarded by now, even though the agitprop often agitated in the right direction; or have we forgotten that workers, at some point, were truly horribly exploited and that the 8-hour workshift was a bloody struggle? But, being able to quickly sift through caricatures - the fat, capitalist factory owner, the well-groomed, pigheaded stockholders slobbering on their fat cigars - and process the easy distinctions between collective good and the individual selfishness, means we can concentrate on rhythm. On how these thin caricatures that should have been harmless, yet are charged with a power that moves and affects.

It's about the mechanisms that control the image; it is a unique opportunity to have this film, it shows the very image being controlled. The end of the first part, with the shot of huge factory machinery whirring into motion as already the uprising is being set into motion; and later, the hand of the cruel stockholder superimposed over the crowd of strikers, clutching, controlling.

Eisenstein is so adept in his touch that the film is, at times, action, comedy, chamber drama, detective film, policier, paean, sobering catastrophe.

The most amazing sequence; we are with the strikers in an outdoors gathering, as the leader is laying down their demands, yet immediately transported to the lavish mansion of the stockholders as they read them with anger; there is some talk and eventually, satisfied, gleeful, they break out the drinks, an intertitle informs us of their answer to the demands, a polite, civilized refusal 'after careful consideration', while immediately the mounted police is storming the outdoors camp.

It is a stunning display of cinema, how time and space are contorted to accommodate for our passage through and yet the result is a dialectic between images as eminently designed for the eye - not the mind. We see, ergo we know - and are.

Change; action; seeing. This is the causal chain the Soviets immersed themselves in, looking for the keys that guide vision.

So, these people eventually grew to know more about the mechanisms that control the image than any other group of people anywhere else in history. They were theoreticians, scientists of film, as well as the actual makers; a now extinct combination, much to our dismay. Eisenstein - and Vertov - were key figures; I mean, here was a man who studied Japanese ideograms to understand synthesized image; who discovered that editing to the beats of the human heart affected more.

So, we are talking about a reflexive cinema, about rhythm as opposed to melody. It's just as well with these films that the narrative content is pretty much discarded by now, even though the agitprop often agitated in the right direction; or have we forgotten that workers, at some point, were truly horribly exploited and that the 8-hour workshift was a bloody struggle? But, being able to quickly sift through caricatures - the fat, capitalist factory owner, the well-groomed, pigheaded stockholders slobbering on their fat cigars - and process the easy distinctions between collective good and the individual selfishness, means we can concentrate on rhythm. On how these thin caricatures that should have been harmless, yet are charged with a power that moves and affects.

It's about the mechanisms that control the image; it is a unique opportunity to have this film, it shows the very image being controlled. The end of the first part, with the shot of huge factory machinery whirring into motion as already the uprising is being set into motion; and later, the hand of the cruel stockholder superimposed over the crowd of strikers, clutching, controlling.

Eisenstein is so adept in his touch that the film is, at times, action, comedy, chamber drama, detective film, policier, paean, sobering catastrophe.

The most amazing sequence; we are with the strikers in an outdoors gathering, as the leader is laying down their demands, yet immediately transported to the lavish mansion of the stockholders as they read them with anger; there is some talk and eventually, satisfied, gleeful, they break out the drinks, an intertitle informs us of their answer to the demands, a polite, civilized refusal 'after careful consideration', while immediately the mounted police is storming the outdoors camp.

It is a stunning display of cinema, how time and space are contorted to accommodate for our passage through and yet the result is a dialectic between images as eminently designed for the eye - not the mind. We see, ergo we know - and are.

Russian master Sergei Eisenstein's first feature film is a tour-de-force of cinematic technique. He appears to have a pretty speedy learning curve, beginning straight away with a picture that is confidently crafted and extremely watchable even today.

With the exception of Que Viva Mexico (which he made outside Russia), this is Eisenstein's purest film, the one most free from the constraints of the Bolshevik propaganda machine. There is one mention of the Bolsheviks, but it's inconsequential. This is essentially a film about self-organisation of the workers a placeless and timeless story which acts as a case study in how a strike can begin, how it can be made successful and how it can be defeated.

Strike has an incredibly exhilarating pace to it and, aside from its political message works as a pure action film. Perhaps unusually for a debut film, this is also the closest Eisenstein came to making a comedy. In a style that would mark all his films, he characterises the villains of the piece the factory management, police chiefs and government bureaucrats as exaggerated and often ridiculous figures of fun. The factory owner is the stereotypical capitalist a top hat-wearing fat controller.

As usual with early Soviet cinema, Strike is essentially characterless. The story is told through the masses, and the proletariat as a whole is the hero. Eisenstein was ideally suited to this, as even in this early film he gives an unprecedented realism to the crowd scenes, and uses every technique at his disposal to create drama from mass action. Eisenstein also demonstrates early on that he has the rather unusual talent of directing large groups of people being massacred. It's an image that would crop up in nearly all of his films.

The only real weakness of Strike is that it too often slips into pretentiousness. Some of the techniques are little more than showing off. There are just a few too many superimpositions and mirror images shots. The symbolism is also often a little too heavy-handed and abstract the two kids dancing on the table during the interrogation scene certainly baffles me; god knows what the Russian public made of it.

Eisenstein is often described as a pioneer, a founding father of film technique. However, in truth most of the techniques he used had been developed earlier, in particular by D.W. Griffith. It's just that Eisenstein pushed the possibilities of editing to their extreme. He's more of a maverick than a pioneer, as there really has been no-one like him since. Having said that, I can identify three new uses of the editing process that Eisenstein invented with Strike.

Firstly, he often uses a sequence of similar shots to give the impression of the same action being done by lots of people. For example, three shots of tools being thrown to the ground tells us quickly and effectively, in the context of the scene, that the entire workforce is downing tools. Secondly, he edits rhythmically to punctuate action. For example, a quick, dynamic action like someone throwing a punch or a door slamming shut will be punctuated by a film cut, giving it much more impact. This is particularly effective in silent film, as the jarring cuts mean you can almost hear the action in your head.

The third editing technique debuted here was the most abstract and the least influential. Whereas Griffith would edit back and forth between two or more literally related scenes (for example, between someone in trouble and someone coming to rescue them) to build up tension, Eisenstein edits back and forth between unrelated images to create a metaphor. The well-known example of this in Strike is the cutting from the workers being gunned down to shots of cattle being slaughtered the cattle dying is nothing to do with the plot, but it makes a point. It's a clever idea, but one that was rarely imitated as it breaks up the flow of a film's narrative.

On a totally different note, a little hobby of mine is spotting modern day look-alikes in old films, and Strike has one of my favourites. The king of the beggars is a dead ringer for Shane MacGowan, right down to the missing teeth. Amazing.

Strike has to be one of the most remarkable and mould-breaking debut films of all time. It's not quite up to the level of masterpiece yet, but it's an incredible experience and genuinely gripping entertainment.

With the exception of Que Viva Mexico (which he made outside Russia), this is Eisenstein's purest film, the one most free from the constraints of the Bolshevik propaganda machine. There is one mention of the Bolsheviks, but it's inconsequential. This is essentially a film about self-organisation of the workers a placeless and timeless story which acts as a case study in how a strike can begin, how it can be made successful and how it can be defeated.

Strike has an incredibly exhilarating pace to it and, aside from its political message works as a pure action film. Perhaps unusually for a debut film, this is also the closest Eisenstein came to making a comedy. In a style that would mark all his films, he characterises the villains of the piece the factory management, police chiefs and government bureaucrats as exaggerated and often ridiculous figures of fun. The factory owner is the stereotypical capitalist a top hat-wearing fat controller.

As usual with early Soviet cinema, Strike is essentially characterless. The story is told through the masses, and the proletariat as a whole is the hero. Eisenstein was ideally suited to this, as even in this early film he gives an unprecedented realism to the crowd scenes, and uses every technique at his disposal to create drama from mass action. Eisenstein also demonstrates early on that he has the rather unusual talent of directing large groups of people being massacred. It's an image that would crop up in nearly all of his films.

The only real weakness of Strike is that it too often slips into pretentiousness. Some of the techniques are little more than showing off. There are just a few too many superimpositions and mirror images shots. The symbolism is also often a little too heavy-handed and abstract the two kids dancing on the table during the interrogation scene certainly baffles me; god knows what the Russian public made of it.

Eisenstein is often described as a pioneer, a founding father of film technique. However, in truth most of the techniques he used had been developed earlier, in particular by D.W. Griffith. It's just that Eisenstein pushed the possibilities of editing to their extreme. He's more of a maverick than a pioneer, as there really has been no-one like him since. Having said that, I can identify three new uses of the editing process that Eisenstein invented with Strike.

Firstly, he often uses a sequence of similar shots to give the impression of the same action being done by lots of people. For example, three shots of tools being thrown to the ground tells us quickly and effectively, in the context of the scene, that the entire workforce is downing tools. Secondly, he edits rhythmically to punctuate action. For example, a quick, dynamic action like someone throwing a punch or a door slamming shut will be punctuated by a film cut, giving it much more impact. This is particularly effective in silent film, as the jarring cuts mean you can almost hear the action in your head.

The third editing technique debuted here was the most abstract and the least influential. Whereas Griffith would edit back and forth between two or more literally related scenes (for example, between someone in trouble and someone coming to rescue them) to build up tension, Eisenstein edits back and forth between unrelated images to create a metaphor. The well-known example of this in Strike is the cutting from the workers being gunned down to shots of cattle being slaughtered the cattle dying is nothing to do with the plot, but it makes a point. It's a clever idea, but one that was rarely imitated as it breaks up the flow of a film's narrative.

On a totally different note, a little hobby of mine is spotting modern day look-alikes in old films, and Strike has one of my favourites. The king of the beggars is a dead ringer for Shane MacGowan, right down to the missing teeth. Amazing.

Strike has to be one of the most remarkable and mould-breaking debut films of all time. It's not quite up to the level of masterpiece yet, but it's an incredible experience and genuinely gripping entertainment.

In the Soviet Union in 1903, the workers of a factory are tired of poor wages, hard living, and harsh treatment by their superiors. Talk of a strike is rife, and when one innocent worker is accused of theft, he hangs himself on the production line and unwittingly becomes a martyr. The strike is decided, and the workers gather in masses to discuss their terms. Meanwhile, the fat cats upstairs are in uproar that the strike has been called, and employ a number of secret agents with animal code names to infiltrate, brutalise and spy on the strikers. As the workers begin to fight amongst themselves, the bosses tactics become increasingly brutal, especially when the police are called in.

Sergei Eisenstein is one of the Soviet Union's greatest ever filmmakers, and arguably one the world's greatest. This was his first feature-length film (he made The Battleship Potemkin later that year, one of the best and most influential films ever made) and his trickery and style is awe- inspiring, given his inexperience and the fact that cinema was still in its early stages. The most effective technique Eisenstein plays is in the early scenes, where he juxtaposes different animals with the key players (Eisenstein was known as the 'King of Montage'). For example, there is an owl, always watching, thinking and cunning, turning into a wild-eye spy; a fox, misleadingly beautiful and sly, becoming a shapeshifting and handsome con-artist - and dancing bears, that portray the workers. The use of this is at its most powerful at the end, when the police move in to overthrow the strike, cut with scenes of a cow having its throat cut, blood gushing out of its wound as it slowly dies.

It's an incredibly stylish piece for its day and moves along at an alarming pace, even when compared to some films today. It never slows down to develop any characters, instead using its revolutionary and Communist themes to play the main role, with the characters being mere pawns in a more important overlying theme. It's clear where Eisenstein's stance is, which does also work against the film. The factory bigwigs are no more than faceless fat men in expensive suits, drinking champagne and smoking cigars all day, laughing at the misfortune of the workers. There is also a scene where one wipes his shoes clean with the workers wage demands. By today's standards, it seems a bit stereotypical, and the metaphors quite obvious. But this is an alarmingly stylish debut from a truly great film-maker, that is both exciting, and come the end, really quite shocking.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

Sergei Eisenstein is one of the Soviet Union's greatest ever filmmakers, and arguably one the world's greatest. This was his first feature-length film (he made The Battleship Potemkin later that year, one of the best and most influential films ever made) and his trickery and style is awe- inspiring, given his inexperience and the fact that cinema was still in its early stages. The most effective technique Eisenstein plays is in the early scenes, where he juxtaposes different animals with the key players (Eisenstein was known as the 'King of Montage'). For example, there is an owl, always watching, thinking and cunning, turning into a wild-eye spy; a fox, misleadingly beautiful and sly, becoming a shapeshifting and handsome con-artist - and dancing bears, that portray the workers. The use of this is at its most powerful at the end, when the police move in to overthrow the strike, cut with scenes of a cow having its throat cut, blood gushing out of its wound as it slowly dies.

It's an incredibly stylish piece for its day and moves along at an alarming pace, even when compared to some films today. It never slows down to develop any characters, instead using its revolutionary and Communist themes to play the main role, with the characters being mere pawns in a more important overlying theme. It's clear where Eisenstein's stance is, which does also work against the film. The factory bigwigs are no more than faceless fat men in expensive suits, drinking champagne and smoking cigars all day, laughing at the misfortune of the workers. There is also a scene where one wipes his shoes clean with the workers wage demands. By today's standards, it seems a bit stereotypical, and the metaphors quite obvious. But this is an alarmingly stylish debut from a truly great film-maker, that is both exciting, and come the end, really quite shocking.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

It takes place during the 1912 Factory Strike in Russia. This was the brilliant debut of Sergei Eisenstein which introduced the idea of montage. Done before Potemkin, Stachka/Strike(1925) is a film about the struggle of the working class against the Tsar. The film showed of things to come for the career of Eisenstein. This was to be part of a series of films concerning the events that led to the 1917 Revolution. He shows the working class as the main protagonist in Strike. Was co-written by frequent co-writer Grigori Aleksandrov.

Stachka and Battleship Potemkin would be the only films in which Eisenstein would have complete artistic control. Like Potemkin, it also features a grand massacre sequence. Eisenstein's direction is nothing short of first class. October(1927) can be looked upon as a sequel to Strike. The images of this is an example of why the silent period was the last truly great era of visual filmmaking. Strike would be the first of many great movies from a master artist. A fine scene is the superimposition of a slaughtered bull over a scene of massacred workers.

Stachka and Battleship Potemkin would be the only films in which Eisenstein would have complete artistic control. Like Potemkin, it also features a grand massacre sequence. Eisenstein's direction is nothing short of first class. October(1927) can be looked upon as a sequel to Strike. The images of this is an example of why the silent period was the last truly great era of visual filmmaking. Strike would be the first of many great movies from a master artist. A fine scene is the superimposition of a slaughtered bull over a scene of massacred workers.

Not Eisensteins most famous film, but it was his first and it's important in the history of cinema. The montage is brilliant and the inventive camerawork alone make it endlessly important. A routine story about workers striking put against the satire of the aristocracy, it seems most of the Russian silent films were like this, but the story isn't whats important in these films, it's the camera use. Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Kuleshov, these filmmakers are possibly the most important group of directors ever.

Did you know

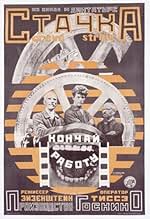

- TriviaStrike (Russian: Strike (1925)) is a Soviet silent propaganda film edited and directed by Sergei Eisenstein. Originating as one entry out of a proposed seven-part series titled "Towards Dictatorship of the Proletariat," Strike was a joint collaboration between the Proletcult Theatre and the film studio Goskino. As Eisenstein's first full-length feature film, it marked his transition from theatre to cinema, and his next film Battleship Potemkin (1925) (Russian: Bronenosets Potyomkin) emerged from the same film cycle.

- GoofsThe story is set in 1903. Throughout the film, automobiles from the 1920s appear on streets. One is the 1920s auto that the worker (who stole the administrators' posted reply to workers' demands) tried to use to escape police goons during a nighttime rainstorm. When upper-class women appear, they are wearing contemporary 1920s fashions, and the popular music that's on the sound track is also from the 1920s.

- Quotes

Title Card: At the factory, all is calm. BUT. The boys are restless.

- Alternate versionsThe film was restored at Gorky Film Studio in 1969.

- ConnectionsEdited into Ten Days That Shook the World (1967)

- How long is Strike?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Runtime1 hour 22 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content