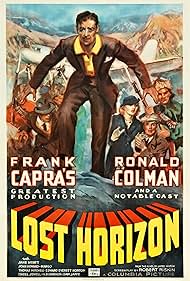

When a revered diplomat's plane is diverted and crashes in the peaks of Tibet, he and the other survivors are guided to an isolated monastery at Shangri-La, where they wrestle with the invit... Read allWhen a revered diplomat's plane is diverted and crashes in the peaks of Tibet, he and the other survivors are guided to an isolated monastery at Shangri-La, where they wrestle with the invitation to stay.When a revered diplomat's plane is diverted and crashes in the peaks of Tibet, he and the other survivors are guided to an isolated monastery at Shangri-La, where they wrestle with the invitation to stay.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Won 2 Oscars

- 6 wins & 6 nominations total

Norman Ainsley

- Embassy Club Steward

- (uncredited)

Chief John Big Tree

- Porter

- (uncredited)

Wyrley Birch

- Missionary

- (uncredited)

Beatrice Blinn

- Passenger

- (uncredited)

Hugh Buckler

- Lord Gainsford

- (uncredited)

Sonny Bupp

- Boy Being Carried to Plane

- (unconfirmed)

- (uncredited)

John Burton

- Wynant

- (uncredited)

Tom Campbell

- Porter

- (uncredited)

Matthew Carlton

- Pottery Maker

- (uncredited)

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

I think I was about seven or eight years old when I first saw this film, and has always lingered in the back of my mind. This is pure movie magic of a rare kind, and it is surprising how well it holds up today. The story is handled with just the right balance of seriousness and humour, with fine performances throughout, and the timeless message it sends is truly profound. The middle part may be lacking a bit in pacing, but it is a minor quibble, since this, for my money, is a masterpiece. And it still looks great, with impressive set design and an abundance of atmosphere. The finale is simply sublime, and stays in the mind for a long time afterwards, one of my favorite movie moments of all time. A movie everyone should see.

Fantasy filled film that shows the different facaets of human nature. Beautifully conceived by Frank Capra whose brilliant at making films with sentlemenity as main force. A masterpiece which was brutally cut during its threaitcal run and only recently has the film been somewhat restored. Thus, the complete version of Lost Horizon(1937) is one of many lost classics in history of film. Acting is excellent with everyone giving deep performances. An wonderful story with intriquing spirital symbolisms. Ronald Colman does a marvalous job as the good natured and tolerate Robert Conway. Personally I perfer Lost Horizons(1937) over Its a Wonderful Life(1946) because the main character in the former is more complex.

One of my favorite books growing up was James Hilton's classic 1933 book, "Lost Horizon", and I believe it motivated a great deal of my current wanderlust. Even though I have had the misfortune of seeing the disastrous 1973 musical remake when I was young, the original 1937 film adaptation has been a film I have wanted to see for years, but for whatever reason, it was next to impossible to uncover. Apparently, bastardized versions have shown up on TV through the years. Now we are fortunate to have this 1999 restoration spearheaded by UCLA film archivist Robert Gitt to match as closely as possible to Frank Capra's original 132-minute running time.

Similar to what was done with George Cukor's "A Star Is Born", "Lost Horizon" is presented with its complete soundtrack, but missing footage had to be found through other sources, even 16-mm prints recorded from TV broadcasts, and in a few scenes, production stills were sadly the only option to fill in the gaps. Consequently, there is a variable quality to the print, but when one thinks that much of this footage could have been completely lost, the visual lapses are more than forgivable. Now that I have seen Capra's vision of the book, I can now understand why it's a cinematic classic though I have to concede not as timeless as one would hope.

The fanciful plot centers on Robert Conway, a top-level English diplomat about to become the Foreign Secretary, who helps refugees and assorted others from war-ravaged China. A motley crew of passengers led by Conway boards a plane that is skyjacked toward the Himalayas where it crash lands in a desolate spot of Tibet. They are eventually met by a sect of locals who takes them to a paradise called Shangri-La. The focus of the story then becomes how each of the plane survivors responds to this utopian existence. With his instantly recognizable mellifluous tone, Ronald Colman is perfectly cast as Conway, the only one who embraces this seemingly perfect haven from the outset. He captures the natural curiosity and open romanticism of his character with his trademark erudite manner.

The rest of the cast is a gallery of stock characters fleshed out by the variable quality of the performances. H.B. Warner plays Chang with the requisite serenity of his vague, mysterious character; and Jane Wyatt - two decades before playing the perfect suburban wife and mother in "Father Knows Best" - is surprisingly saucy as Sondra, the young schoolteacher who has Conway brought to Shangri-La. She even has a brief nude swimming scene. John Howard unfortunately overplays the thankless role of Conway's obstreperous brother George to the point where I groan every time he appears on screen. A similar feeling comes over me when I see Edward Everett Horton's overly pixilated and fey turn as Lovett and Sam Jaffe's bug-eyed, ethereal High Lama. Isabel Jewell and Thomas Mitchell fare better as a dying prostitute and a fugitive swindler, respectively.

The set designs for the Shangri-La lamasery by Stephen Goossón are intriguing in that they look like a post-modern tribute to Frank Lloyd Wright's prairie architecture, though one could argue that the exteriors also resemble a fancy Miami Beach resort hotel. I also imagine that the isolationist philosophy espoused by the High Lama may have been at odds with pre-WWII patriotic fervor, though the more lingering problem is the racism apparent in the casting (e.g., non-Asians like Warner playing inscrutable Asians) and the portrayal of the Tibetan porters as gun-toting derelicts. However, for all its flaws, the movie has some really stunning camera-work by Joseph Walker, surprisingly masterful special effects (for a near-poverty row studio like Columbia), Dmitri Tiomkin's stirring musical score and a powerful sense of mysticism that gives the film a genuine soul. It is no accident that Capra, the most idealistic of the master filmmakers, helmed this movie because a more cynical mindset could have easily sabotaged the entire venture.

The DVD is a wonderful package. First, there is a fascinating photo montage documentary with narration provided by film historian Kendall Miller, which gives a true feeling of how Capra approached the production. Gitt and film critic Charles Champlin provide audio commentary on an alternate track of the film with Gitt very informative about the exhaustive restoration process and Champlin more in awe of the result. There is even an alternative ending included that Columbia chief Harry Cohn insisted on filming and using upon release, but it had thankfully been dropped two weeks later. This is a genuine treat for cinemaphiles, as there are few films that make such a compelling case for seeking out one's personal utopia.

Similar to what was done with George Cukor's "A Star Is Born", "Lost Horizon" is presented with its complete soundtrack, but missing footage had to be found through other sources, even 16-mm prints recorded from TV broadcasts, and in a few scenes, production stills were sadly the only option to fill in the gaps. Consequently, there is a variable quality to the print, but when one thinks that much of this footage could have been completely lost, the visual lapses are more than forgivable. Now that I have seen Capra's vision of the book, I can now understand why it's a cinematic classic though I have to concede not as timeless as one would hope.

The fanciful plot centers on Robert Conway, a top-level English diplomat about to become the Foreign Secretary, who helps refugees and assorted others from war-ravaged China. A motley crew of passengers led by Conway boards a plane that is skyjacked toward the Himalayas where it crash lands in a desolate spot of Tibet. They are eventually met by a sect of locals who takes them to a paradise called Shangri-La. The focus of the story then becomes how each of the plane survivors responds to this utopian existence. With his instantly recognizable mellifluous tone, Ronald Colman is perfectly cast as Conway, the only one who embraces this seemingly perfect haven from the outset. He captures the natural curiosity and open romanticism of his character with his trademark erudite manner.

The rest of the cast is a gallery of stock characters fleshed out by the variable quality of the performances. H.B. Warner plays Chang with the requisite serenity of his vague, mysterious character; and Jane Wyatt - two decades before playing the perfect suburban wife and mother in "Father Knows Best" - is surprisingly saucy as Sondra, the young schoolteacher who has Conway brought to Shangri-La. She even has a brief nude swimming scene. John Howard unfortunately overplays the thankless role of Conway's obstreperous brother George to the point where I groan every time he appears on screen. A similar feeling comes over me when I see Edward Everett Horton's overly pixilated and fey turn as Lovett and Sam Jaffe's bug-eyed, ethereal High Lama. Isabel Jewell and Thomas Mitchell fare better as a dying prostitute and a fugitive swindler, respectively.

The set designs for the Shangri-La lamasery by Stephen Goossón are intriguing in that they look like a post-modern tribute to Frank Lloyd Wright's prairie architecture, though one could argue that the exteriors also resemble a fancy Miami Beach resort hotel. I also imagine that the isolationist philosophy espoused by the High Lama may have been at odds with pre-WWII patriotic fervor, though the more lingering problem is the racism apparent in the casting (e.g., non-Asians like Warner playing inscrutable Asians) and the portrayal of the Tibetan porters as gun-toting derelicts. However, for all its flaws, the movie has some really stunning camera-work by Joseph Walker, surprisingly masterful special effects (for a near-poverty row studio like Columbia), Dmitri Tiomkin's stirring musical score and a powerful sense of mysticism that gives the film a genuine soul. It is no accident that Capra, the most idealistic of the master filmmakers, helmed this movie because a more cynical mindset could have easily sabotaged the entire venture.

The DVD is a wonderful package. First, there is a fascinating photo montage documentary with narration provided by film historian Kendall Miller, which gives a true feeling of how Capra approached the production. Gitt and film critic Charles Champlin provide audio commentary on an alternate track of the film with Gitt very informative about the exhaustive restoration process and Champlin more in awe of the result. There is even an alternative ending included that Columbia chief Harry Cohn insisted on filming and using upon release, but it had thankfully been dropped two weeks later. This is a genuine treat for cinemaphiles, as there are few films that make such a compelling case for seeking out one's personal utopia.

The second half of the 1930s saw the return of the big picture - bigger budgets, grander ideas, longer runtimes in which to tell a story. But the 30s were also a decade of highly emotional and humanist cinema, fuelled by the hardships of the great depression. Lost Horizon sees what was for the time a rare marriage between burgeoning picture scope, in what was "poverty row" studio Columbia's most expensive production to date, and poignant intimacy in the source novel by James Hilton.

Thank goodness for director Frank Capra, who seemed really able to balance this sort of thing. Capra could be a great showman, composing those beautiful iconic shots to show the magnificent Stephen Goosson art direction off to best advantage. But he also knows how to bring out a touching human story. In some places Capra's camera seems a trifle distant, and is almost voyeuristic as it peeps out through foliage or looming props. But rather than separate us from the people it is done in such a way as to give a kind of respectful distance at times of profound emotion, for example when Ronald Colman comes out of his first meeting with the High Lama. The camera hangs back, just allowing Colman's body language to convey feelings. At other times Capra will go for the opposite tack, and hold someone in a lengthy close-up. In this way we are given to just one facet a character's emotional experience, and it becomes all the more intense for that.

Of course such techniques would be nothing without a good cast. There couldn't really have been anyone better than Ronald Colman for the lead role. Now middle-aged, but still possessed with enough charm and presence to carry a movie, Colman has a slow subtlety to his movements which is nevertheless very expressive. His face, an honest smile but such sad eyes, seems to be filled with all that hope and longing that Lost Horizon is about. Sturdy character actors H.B. Warner and Thomas Mitchell give great support. It's unusual to see comedy player Edward Everett Horton in a drama like this, and comedy players in dramas could often be a sour note in 1930s pictures, but Horton is such a lovable figure and just about close enough to reality to pull it off. The only disappointing performance is that of John Howard, who is overwrought and hammy, but even this works in a way as it makes his antagonistic character seem to be the one who is out of place.

Lost Horizon is indeed a wondrous picture, and one that fulfils its mission statement of being both sweeping and soul-stirring. It appears that Capra, always out for glory, was out to make his second Academy Award Best Picture. But history was to repeat itself. In 1933 he had had his first go at a potential Oscar-winner with The Bitter Tea of General Yen, only for that picture to be ignored and the more modest It Happened One Night to win the plaudits the following year. Lost Horizon won two technical Oscars, but bombed at the box office, but in 1938 the down-to-earth comedy drama You Can't Take it with You topped the box office and won Best Pic.

Lost Horizon was in no way worthy of such a dismissal, and is indeed a bit better than You Can't Take it with You. It was perhaps more than anything a case of bad timing. Audiences were only just starting to get used to two-hour-plus runtimes, especially for movies with such unconventional themes. If you look at contemporary trailers and taglines, you can see it was being pitched as some kind of earth-shattering spectacular, whereas it is more in the nature of an epic drama. For later releases the movie was edited down to as little as 92 minutes. Fortunately, we now have a restored version. The additional material that has been reconstructed is vital for giving depth, not only to the characters, but also to the setting of Shangri-La itself. With hindsight, we can look back on Lost Horizon as a work of real cinematic beauty.

Thank goodness for director Frank Capra, who seemed really able to balance this sort of thing. Capra could be a great showman, composing those beautiful iconic shots to show the magnificent Stephen Goosson art direction off to best advantage. But he also knows how to bring out a touching human story. In some places Capra's camera seems a trifle distant, and is almost voyeuristic as it peeps out through foliage or looming props. But rather than separate us from the people it is done in such a way as to give a kind of respectful distance at times of profound emotion, for example when Ronald Colman comes out of his first meeting with the High Lama. The camera hangs back, just allowing Colman's body language to convey feelings. At other times Capra will go for the opposite tack, and hold someone in a lengthy close-up. In this way we are given to just one facet a character's emotional experience, and it becomes all the more intense for that.

Of course such techniques would be nothing without a good cast. There couldn't really have been anyone better than Ronald Colman for the lead role. Now middle-aged, but still possessed with enough charm and presence to carry a movie, Colman has a slow subtlety to his movements which is nevertheless very expressive. His face, an honest smile but such sad eyes, seems to be filled with all that hope and longing that Lost Horizon is about. Sturdy character actors H.B. Warner and Thomas Mitchell give great support. It's unusual to see comedy player Edward Everett Horton in a drama like this, and comedy players in dramas could often be a sour note in 1930s pictures, but Horton is such a lovable figure and just about close enough to reality to pull it off. The only disappointing performance is that of John Howard, who is overwrought and hammy, but even this works in a way as it makes his antagonistic character seem to be the one who is out of place.

Lost Horizon is indeed a wondrous picture, and one that fulfils its mission statement of being both sweeping and soul-stirring. It appears that Capra, always out for glory, was out to make his second Academy Award Best Picture. But history was to repeat itself. In 1933 he had had his first go at a potential Oscar-winner with The Bitter Tea of General Yen, only for that picture to be ignored and the more modest It Happened One Night to win the plaudits the following year. Lost Horizon won two technical Oscars, but bombed at the box office, but in 1938 the down-to-earth comedy drama You Can't Take it with You topped the box office and won Best Pic.

Lost Horizon was in no way worthy of such a dismissal, and is indeed a bit better than You Can't Take it with You. It was perhaps more than anything a case of bad timing. Audiences were only just starting to get used to two-hour-plus runtimes, especially for movies with such unconventional themes. If you look at contemporary trailers and taglines, you can see it was being pitched as some kind of earth-shattering spectacular, whereas it is more in the nature of an epic drama. For later releases the movie was edited down to as little as 92 minutes. Fortunately, we now have a restored version. The additional material that has been reconstructed is vital for giving depth, not only to the characters, but also to the setting of Shangri-La itself. With hindsight, we can look back on Lost Horizon as a work of real cinematic beauty.

Along with A TALE OF TWO CITIES, THE PRISONER OF ZENDA, and THE LIGHT THAT FAILED, LOST HORIZON represented the best performance possible out of Ronald Colman. And his Robert Conway is the most modern of them (up to the time the films were made). LOST HORIZON is set (as James Hilton intended) in the 1930s, in war torn China. It is not the only reference in the story to the 1930s that Hilton puts into his fable of a paradise on earth.

Hilton had reason to fear about the world he lived in. The Great War (as the First World War was generally called in the 1930s) was still a savage and recent nightmare. The 1920s and 1930s saw dictatorships seize control of European and Asian state, and Democracy retreating everywhere. "Look at the world", says the High Lama (Sam Jaffe), "Is anything worse?" The High Lama is correct - the world is collapsing, and the so-called panaceas (Communist Russia, Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Spain, Imperial Japan and it's "Greater Asiatic Co-Prosperity Sphere") are worse than the seeming ineptitude and drift in badly divided France, weakened Britain, and recovering American.

Hilton took Conway, his brother George, Professor Edward Everett Horton, suspiciously quiet businessman Thomas Mitchell, and consumptive Isabel Elsom to an oasis (possibly the oasis) on that troubled old earth - Shangri La, or "the valley of the Blue Moon") where contentment and peace reigned and people could live, if not forever, far longer and more happily than in say 1937 Germany, Britain, France, Russia, Italy, the U.S., or Japan.

On the whole Capra catches the spirit of the novel - his sets were dismissed as being far to simplistic, but as simplicity is the hallmark of life at Shangri-La the critics seemed to miss the point. As a matter of fact, his sets (in a temperate valley in the Himalayas - a real impossibility) are more acceptable than the idiocies of the future world in the contemporary science fiction film THINGS TO COME, where H.G.Wells believes we should live in cities built in caves.

The acting is very good, particularly Sam Jaffe's ancient High Lama (always shot in shadows). Remember, he is over two hundred years old. Today, because Jaffe had a long career in Hollywood (despite being blacklisted in the 1950s), we think of him as an old man in THE ASPHALT JUNGLE or as "Dr. Zorba" in the series BEN CASEY. So we think he must have looked old in real life when LOST HORIZON was shot. Actually, he was in his thirties or forties, so he was not that old. But he gave a performance that suggested he was an old man.

Another member of the cast that I would wish to bring up for consideration is John Howard. He is not recalled by film fans too much, but Mr. Howard was a good, competent actor. That he played Hugh "Bulldog" Drummond in a series of "B" features in the late thirties makes it ironic that he played the younger brother of Ronald Colman here, who had begun the talking picture segment of his career with the same role. Howard does not have a British accent, but he does show the adoration of the younger brother for his famous sibling, and the growing anger and contempt he develops when brother Robert fails to plan for their leaving this prison they were dragged to - note how he wants to return with a bomber to destroy Shangri-La. It is one of the two roles in major films that John Howard is remembered for, the other being "George Kittridge", the erstwhile fiancé of Tracy Lord (Katherine Hepburn) in THE PHILADELPHIA STORY, who is pushed aside by both Cary Grant and James Stewart.

As it is one of Howard's best roles, it is nice that when the film was restored (as well as possible) in the 1980s, Howard (one of the three surviving cast members) was able to appreciate it - many of the missing sequences were his scenes. Howard was very happy at the restoration result.

Now, one or two notes that may help appreciate the film a little more. Who is Robert Conway supposed to be? He is called, by the High Lama, "Conway, the empire builder." He is supposedly able to do impossible things - hence the admiration of his brother. When he returns to Shangri-La at the end, the comment of the man telling the story is that Conway's journeys by himself back to his valley was beyond what ordinary men could do. So who is Conway? Well, in 1937, the model for Robert Conway was dead, from a motorcycle accident, for two years. It was, of course, Thomas Edward Lawrence "of Arabia", who had never been in Tibet (officially, anyway) but had served time in the Indian subcontinent area on government business in the 1920s. Quite a model for an empire builder.

The character played by Thomas Mitchell is also based on a real person. Harry Barnard's real name (which I have forgotten) is that of an international financier whose vast empire collapsed ruining thousands of investors. It turns out Mitchell's character is based on Samuel Insull, a mid western utilities empire builder (out of Chicago) whose financial doings brought about his collapse in the Great Depression. Insull fled in disguise to Greece, but was found on a dirty freighter, and returned to the U.S. (where he would stand trial for fraud, but be acquitted). Edward Everett Horton's anger at Mitchell when he learned the latter's identity is understandable. Mitchell's involvement in installing new pipes in Shangri-La mirrors Insull's early days, when he was an electrician, and an assistant to Thomas Edison.

The use of these two real figures as the basis of the characters helped contemporary audiences to accept the background of the plot of the film.

Hilton had reason to fear about the world he lived in. The Great War (as the First World War was generally called in the 1930s) was still a savage and recent nightmare. The 1920s and 1930s saw dictatorships seize control of European and Asian state, and Democracy retreating everywhere. "Look at the world", says the High Lama (Sam Jaffe), "Is anything worse?" The High Lama is correct - the world is collapsing, and the so-called panaceas (Communist Russia, Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Spain, Imperial Japan and it's "Greater Asiatic Co-Prosperity Sphere") are worse than the seeming ineptitude and drift in badly divided France, weakened Britain, and recovering American.

Hilton took Conway, his brother George, Professor Edward Everett Horton, suspiciously quiet businessman Thomas Mitchell, and consumptive Isabel Elsom to an oasis (possibly the oasis) on that troubled old earth - Shangri La, or "the valley of the Blue Moon") where contentment and peace reigned and people could live, if not forever, far longer and more happily than in say 1937 Germany, Britain, France, Russia, Italy, the U.S., or Japan.

On the whole Capra catches the spirit of the novel - his sets were dismissed as being far to simplistic, but as simplicity is the hallmark of life at Shangri-La the critics seemed to miss the point. As a matter of fact, his sets (in a temperate valley in the Himalayas - a real impossibility) are more acceptable than the idiocies of the future world in the contemporary science fiction film THINGS TO COME, where H.G.Wells believes we should live in cities built in caves.

The acting is very good, particularly Sam Jaffe's ancient High Lama (always shot in shadows). Remember, he is over two hundred years old. Today, because Jaffe had a long career in Hollywood (despite being blacklisted in the 1950s), we think of him as an old man in THE ASPHALT JUNGLE or as "Dr. Zorba" in the series BEN CASEY. So we think he must have looked old in real life when LOST HORIZON was shot. Actually, he was in his thirties or forties, so he was not that old. But he gave a performance that suggested he was an old man.

Another member of the cast that I would wish to bring up for consideration is John Howard. He is not recalled by film fans too much, but Mr. Howard was a good, competent actor. That he played Hugh "Bulldog" Drummond in a series of "B" features in the late thirties makes it ironic that he played the younger brother of Ronald Colman here, who had begun the talking picture segment of his career with the same role. Howard does not have a British accent, but he does show the adoration of the younger brother for his famous sibling, and the growing anger and contempt he develops when brother Robert fails to plan for their leaving this prison they were dragged to - note how he wants to return with a bomber to destroy Shangri-La. It is one of the two roles in major films that John Howard is remembered for, the other being "George Kittridge", the erstwhile fiancé of Tracy Lord (Katherine Hepburn) in THE PHILADELPHIA STORY, who is pushed aside by both Cary Grant and James Stewart.

As it is one of Howard's best roles, it is nice that when the film was restored (as well as possible) in the 1980s, Howard (one of the three surviving cast members) was able to appreciate it - many of the missing sequences were his scenes. Howard was very happy at the restoration result.

Now, one or two notes that may help appreciate the film a little more. Who is Robert Conway supposed to be? He is called, by the High Lama, "Conway, the empire builder." He is supposedly able to do impossible things - hence the admiration of his brother. When he returns to Shangri-La at the end, the comment of the man telling the story is that Conway's journeys by himself back to his valley was beyond what ordinary men could do. So who is Conway? Well, in 1937, the model for Robert Conway was dead, from a motorcycle accident, for two years. It was, of course, Thomas Edward Lawrence "of Arabia", who had never been in Tibet (officially, anyway) but had served time in the Indian subcontinent area on government business in the 1920s. Quite a model for an empire builder.

The character played by Thomas Mitchell is also based on a real person. Harry Barnard's real name (which I have forgotten) is that of an international financier whose vast empire collapsed ruining thousands of investors. It turns out Mitchell's character is based on Samuel Insull, a mid western utilities empire builder (out of Chicago) whose financial doings brought about his collapse in the Great Depression. Insull fled in disguise to Greece, but was found on a dirty freighter, and returned to the U.S. (where he would stand trial for fraud, but be acquitted). Edward Everett Horton's anger at Mitchell when he learned the latter's identity is understandable. Mitchell's involvement in installing new pipes in Shangri-La mirrors Insull's early days, when he was an electrician, and an assistant to Thomas Edison.

The use of these two real figures as the basis of the characters helped contemporary audiences to accept the background of the plot of the film.

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaThe year after this film was released the owner of a prosperous theater chain hired an architect who designed a mansion that was inspired by the Shangri-La lamasery in this film. Located in Denver, Colorado, it still exists today.

- GoofsEchoing the words of the critic, James Agate: 'The best film I've seen for ages, but will somebody please tell me how they got the grand piano along a footpath on which only one person can walk at a time with rope and pickaxe and with a sheer drop of three thousand feet or so?'

- Crazy creditsBob Gitt of the UCLA Film & Television Archives claims the original opening sequence in 1937 had title cards "Conway has been sent to evacuate ninety white people before they're butchered in a local revolution" was changed in 1942 for a special reissue during WWII. The title cards read "before innocent Chinese people were butchered by Japanese hordes." This was to bolster propaganda against the Japanese.

- Alternate versionsSome of the music in the restored version is dubbed into different sections than the ones in the 118 minute cut version. For example, the moment in which Robert Conway ('Ronald Colman') discovers that the High Lama is really Father Perrault i accompanied by soft music in the cut version, while in the restored version this moment is played with no music.

- ConnectionsEdited from Storm Over Mont Blanc (1930)

- SoundtracksWiegenlied (Lullaby) Op. 49 No. 4

(1868) (uncredited)

Composed by Johannes Brahms

English translator unknown

Sung a cappella by children at Shangri-La

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Official site

- Languages

- Also known as

- Horizontes perdidos

- Filming locations

- Production company

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Budget

- $4,000,000 (estimated)

- Runtime2 hours 12 minutes

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.37 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content